Axiom Verge: Empty Space

What could any Other know of the Up-and-Out? What Other could look at the biting acid beauty of the stars in open Space? What could they tell of the Great Pain, which started quietly in the marrow, like an ache, and proceeded by the fatigue and nausea of each separate nerve cell, brain cell, touchpoint in the body, until life itself became a terrible aching hunger for silence and for death? — Cordwainer Smith, Scanners Live in Vain

A few years ago, a close friend of mine passed away at a very young age. I was emotionally gutted, and almost without thinking I found myself playing Iron Lore’s Titan Quest for eight hours a day, every day for a solid month. “My fugue state,” I called it. Total immersion inside a video game was a way for me to be alone with my thoughts. Alone from my thoughts. And despite the horrible circumstances under which I played it, I don’t hate Titan Quest. Quite the opposite. It was exactly what I needed at a difficult time in my life. I was alone and frightened, and the game helped me find my way through.

A few years ago, a close friend of mine passed away at a very young age. I was emotionally gutted, and almost without thinking I found myself playing Iron Lore’s Titan Quest for eight hours a day, every day for a solid month. “My fugue state,” I called it. Total immersion inside a video game was a way for me to be alone with my thoughts. Alone from my thoughts. And despite the horrible circumstances under which I played it, I don’t hate Titan Quest. Quite the opposite. It was exactly what I needed at a difficult time in my life. I was alone and frightened, and the game helped me find my way through.

Everyone is frightened of being alone. There’s a very good reason the fear of empty space is such a common sci-fi trope: what could be scarier than nothing? After all, the greater the isolation, the deeper the fear. So if the human mind could ever actually wrap itself around the infinite void, it would snap like a dry twig in a strong breeze.

Game designers are certainly afraid of nothing; that’s why games almost always ape the macho swagger of Aliens’ weaponized space marines instead of the first Alien’s staccato terror. Action is considered a safer bet than inaction. Video games are your friend who won’t shut up, afraid that any small break in the conversation could be the crack that grows to end your friendship.

Game designers are certainly afraid of nothing; that’s why games almost always ape the macho swagger of Aliens’ weaponized space marines instead of the first Alien’s staccato terror. Action is considered a safer bet than inaction. Video games are your friend who won’t shut up, afraid that any small break in the conversation could be the crack that grows to end your friendship.

But games brave enough to embrace isolation and loneliness have found it freeing, even relaxing. Consider Wander riding Argo through the wastelands of Shadow of the Colossus, or Link sailing between islands in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. The silent and austere alien landscapes of Out of this World. And of course the original Metroid, with its unexplained dark spaces, its uncharted universe, and unforgettable Hip Tanaka score.

The first Metroid is a game that understands and embraces the awesome power of empty space. I’ve always preferred the tone of the first two Metroid games to Super Metroid and the games that came afterward. The first two games present a perfect solitude, with bounty hunter Samus Aran as the only person left in a forgotten universe, exploring worlds thousands of millennia dead. Once Super Metroid introduces other characters– scientists, space pirates, furry friends–its world suffers for it.

The first Metroid is a game that understands and embraces the awesome power of empty space. I’ve always preferred the tone of the first two Metroid games to Super Metroid and the games that came afterward. The first two games present a perfect solitude, with bounty hunter Samus Aran as the only person left in a forgotten universe, exploring worlds thousands of millennia dead. Once Super Metroid introduces other characters– scientists, space pirates, furry friends–its world suffers for it.

Axiom Verge, like other “Metroidvania” games, is ultimately about exploring and defining the limits of empty space. The player starts from absolute zero: no abilities, no map, no knowledge of how they got here or how far they can go. The universe of the game is then filled in over the course of several hours, creatio ex nihilo. Every power-up, weapon and map percentage point is a candle in the dark the player uses to illuminate the unknown.

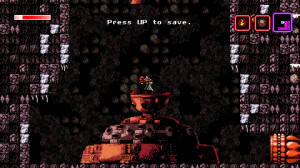

These games and worlds lend themselves to trancelike, meditative play. We cross and recross the map until the path of our travels becomes an unreadable palimpsest. The moment-to-moment play becomes almost automatic, like counting beads on a rosary, as we shift our focus to the higher-level mysteries of the game world. We mash the fire button over and over like a soothing nembutsu. We wander, uncertain where to go next, but trusting the path forward, the next area, will eventually be known.

These games and worlds lend themselves to trancelike, meditative play. We cross and recross the map until the path of our travels becomes an unreadable palimpsest. The moment-to-moment play becomes almost automatic, like counting beads on a rosary, as we shift our focus to the higher-level mysteries of the game world. We mash the fire button over and over like a soothing nembutsu. We wander, uncertain where to go next, but trusting the path forward, the next area, will eventually be known.

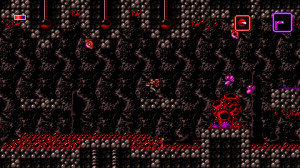

I love these games: Metroid, Castlevania, Metroidvania. I love feeling like I’m the first person to set foot in an environment for 500 years. Axiom Verge’s NES-style retro graphics are a perfect visual metaphor to create a forgotten world. The metaphor is further compounded by the way the game integrates “glitchy” graphics into its enemies and world design. The decayed, flickering world of Axiom Verge is a game you played 30 years ago but now can’t quite remember the name of.

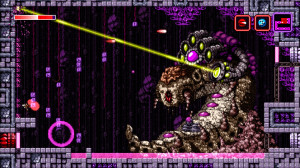

The game is full of weird creatures and bosses, and your character has dozens of tools and weapons at his disposal. They’re clever and creative, and do an excellent job of making the familiar gameplay feel fresh and new. But they’re never the point. The point is there in the space between the map and the void, in the way your effort and exploration transmutes nothing into something, room-by-room, tile-by-tile.

The game is full of weird creatures and bosses, and your character has dozens of tools and weapons at his disposal. They’re clever and creative, and do an excellent job of making the familiar gameplay feel fresh and new. But they’re never the point. The point is there in the space between the map and the void, in the way your effort and exploration transmutes nothing into something, room-by-room, tile-by-tile.

Playing a game as well-crafted as Axiom Verge is its own form of alchemy. A game isn’t just a thing that we watch or a place that we visit. Games are verbs: a thing that we do, or that is done to us. But by whom? Like the now-classic Cave Story, Axiom Verge is the work of one man; Tom Happ spent five years placing every pixel and every object. Tom wrote the story, composed the music, made sure the bosses were fun and the weapons were balanced. Tom built the world first so that I could have the pleasure of building it once more. Five years is a long time to work on one thing. I can’t help but wonder if he sometimes felt alone.

Playing a game as well-crafted as Axiom Verge is its own form of alchemy. A game isn’t just a thing that we watch or a place that we visit. Games are verbs: a thing that we do, or that is done to us. But by whom? Like the now-classic Cave Story, Axiom Verge is the work of one man; Tom Happ spent five years placing every pixel and every object. Tom wrote the story, composed the music, made sure the bosses were fun and the weapons were balanced. Tom built the world first so that I could have the pleasure of building it once more. Five years is a long time to work on one thing. I can’t help but wonder if he sometimes felt alone.

When I look at Axiom Verge I can’t help but remember the games of my youth, a time when things seemed simple and games were an unalloyed pleasure. As I grow older, that feeling feels more and more like a half-remembered dream. Working on a high-profile AAA game for years gave me a front-row seat to gamers’ capacity for abuse. And the recent horrors of GamerGate have made it even more challenging to keep the faith. There’ve been times I’ve wondered: what’s the point? Why write, why build, why care at all?

Axiom Verge helped me remember why I fell in love with games in the first place. At their best, they really do create another world. So when I think back to the times in my life I fell deep into a game for weeks or months, maybe I wasn’t as lost or alone as I felt. Maybe those were the times games carried me.