Fantasy Life: Devaluing Violence

The first time I played Fantasy Life, I chose to do so focusing on only two jobs, or “Lives” in the game’s parlance. I would be, I decided, a dedicated Miner who dabbled as a Blacksmith primarily as a way of smelting the minerals I was already collecting and forging better mining equipment for myself. A friend asked, not unreasonably, why I didn’t go for a third Life of Paladin or Mercenary, so that I could make full use of the labor chain from collecting ore, working it into equipment, and putting that equipment into practice.

I said that if I wanted to play a game focusing on battling enemies and collecting drops, I could play almost every other game ever made, and I wanted to focus on what was unique about this game in particular. One of the things I love to see in a game, and which Fantasy Life provides, is the portrayal of the everyday and mundane as heroic. You are not an adventurer in this game; you are a person with a job. The crisis facing the world is described as arising not from any one evil figure, but from a general abandonment of duty and work. The closest thing the game has to a recurring “villain” is a village youth who airily refuses to take up a Life. The highest virtues of the game, both in and out of the story, are a commitment to one’s craft and an open mind to the needs of others; one or the other resolves every conflict in the story.

I said that if I wanted to play a game focusing on battling enemies and collecting drops, I could play almost every other game ever made, and I wanted to focus on what was unique about this game in particular. One of the things I love to see in a game, and which Fantasy Life provides, is the portrayal of the everyday and mundane as heroic. You are not an adventurer in this game; you are a person with a job. The crisis facing the world is described as arising not from any one evil figure, but from a general abandonment of duty and work. The closest thing the game has to a recurring “villain” is a village youth who airily refuses to take up a Life. The highest virtues of the game, both in and out of the story, are a commitment to one’s craft and an open mind to the needs of others; one or the other resolves every conflict in the story.

My friend pointed out that if that was my stance, then theoretically I didn’t have to kill anything to finish the game. I considered this, and after finishing my “normal” playthrough, started the game anew as a strict pacifist. Not only is it possible to complete the game this way, but doing so yields a number of insights as to how the game’s approach to violence is reflected in its scenario, world design, and economy.

THE RULES OF PLAY

My terms for “completing” Fantasy Life as a pacifist were thus: I had to reach both the end of the storyline, which meant completing each Tale of Lunares chapter and seeing the credits roll, as well to reach Master in my chosen Life without dabbling in any other profession. I began the game as an Alchemist and completed both these requirements before moving on to master all three gathering Lives, each in turn: Miner, Angler, and Woodcutter. After mastering each Life, I would sell all my creations and tools before applying for the new license, and treat each Life as its own isolated track to ensure that it can be mastered without relying on leveling up other Lives for support.

To master a Life is not to exhaust the possibilities in that Life, but there are several things about that rank (as opposed to the later Hero and Legend ranks) that mark it as the natural endpoint: it’s the rank at which you’re treated to a special celebration, it’s the rank that unlocks the full inventory of the shops specific to your Life, it’s the rank where you learn the most powerful skill in your profession, and it’s the rank that the game’s own lore designates as the culmination of the profession: when you finish challenges in your Life, you go to report your progress to your own Master. Items and equipment crafted by post-Master recipes, using post-Master gathered materials, are also generally not in circulation in Reveria’s economy, marking them as something beyond the accepted “upper limit” of the world.

My last stipulation for playing as a pacifist was to accept no assistance in killing monsters. Fantasy Life provides avenues for this if you want it: there are dozens of NPCs you can recruit to join your party to do your fighting for you if you wish, or you could play online with a friend and have them handle the combat. For myself, though, I went solo apart from the times that the storyline forces NPCs into your party, and even then, I took pains to ensure they killed no living thing.

NONVIOLENCE IN THE NARRATIVE

The easiest thing about a nonviolent playthrough of Fantasy Life is making it through the story. Every chapter of the Tale of Lunares plot, without exception, involves going to a new place, having a few interactions with its inhabitants in which your preconceived notions about them are revealed to be wrong, the arrival of a Doomstone that turns the local fauna against you, a brief encounter with said fauna, and finally the righting of long-held misconceptions to bring about peace through better understanding.

The easiest thing about a nonviolent playthrough of Fantasy Life is making it through the story. Every chapter of the Tale of Lunares plot, without exception, involves going to a new place, having a few interactions with its inhabitants in which your preconceived notions about them are revealed to be wrong, the arrival of a Doomstone that turns the local fauna against you, a brief encounter with said fauna, and finally the righting of long-held misconceptions to bring about peace through better understanding.

In practical terms, this mostly means following the red arrow on your map to the next plot marker, reading (or holding the X button to skip) pages and pages of dialogue, and then repeating this process for the next plot marker. There are only two points during any chapter that involve combat, and the game offers alternatives during both.

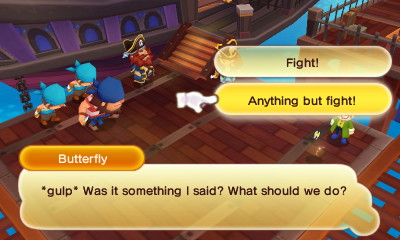

The first point usually comes during the “interactions with the inhabitants” phase, in which one of the locals is being menaced by predators, either animal or human. In every instance of these encounters, the Butterfly (your omnipresent guide through the story) will give you the choice before combat whether you want to engage the predators or choose not to fight. Choosing not to fight, and then confirming your choice, results in a winking fade to black while the Butterfly resolves the conflict for you through mysterious, though statedly peaceful, means.

The Doomstone encounter in every chapter can’t be skipped so easily. However, the encounter design always offers you the unspoken choice of either attacking the creatures affected by the Doomstone (who radiate a shadowy, purple aura) or the nearby Doomstone itself. Destroying the Doomstone brings an end to the fight just as surely as killing the affected creatures, providing a neat way around the rule to “strike no living thing.”

The Doomstone encounter in every chapter can’t be skipped so easily. However, the encounter design always offers you the unspoken choice of either attacking the creatures affected by the Doomstone (who radiate a shadowy, purple aura) or the nearby Doomstone itself. Destroying the Doomstone brings an end to the fight just as surely as killing the affected creatures, providing a neat way around the rule to “strike no living thing.”

These options, both implicit and explicit, are the first hint a player will get at the developers’ quiet determination to ensure that there’s always a nonviolent path forward. The pains they took to make these options available were what made me wonder what else might be possible for the nonviolent player.

NONVIOLENCE IN LIFE

A pacifist play style means limiting yourself. Making a conscious decision not to strike enemies cuts you off from four of the twelve possible Lives from the word go. Beyond that, you cannot reach the post-Master ranks of Hero or Legend in most lives. Crafting classes eventually run into recipes and blueprints which require components that cannot be obtained in any way other than slaying monsters, and gathering classes will find themselves unable to reach certain types of resources that are gated beyond kill barriers.

These limits, however, transform the way the game is played. My pacifist game required tactics and leaned on abilities that I never would have considered in my normal file. The first Life I pursued, Alchemist, is a crafting class which leans heavily on items mostly acquired through monster drops; making progress in this Life meant learning not only which components were sold where, but also keeping track of how much I was paying for those materials and how much profit I was making with each sale of one of my creations. Since I was forced to buy all of my materials rather than go out and kill for them, it was important to make sure I was getting the best return on my investment to forestall the tedium of grinding out one low-margin craft after another.

In all that time, I only ran up against one component which couldn’t be bought but could be collected: the Rainbow Shells that are rarely found in the Nautilus Cave west of Port Puerto. After spending hours of play keeping to civilization, where the shops and Alchemy ateliers were found, having to go out into the wild to collect my own materials felt strange and new again, rather than routine.

In all that time, I only ran up against one component which couldn’t be bought but could be collected: the Rainbow Shells that are rarely found in the Nautilus Cave west of Port Puerto. After spending hours of play keeping to civilization, where the shops and Alchemy ateliers were found, having to go out into the wild to collect my own materials felt strange and new again, rather than routine.

It’s in the three crafting Lives, however, that the mechanics of nonviolence are sharply highlighted, in ways that are by turns both exciting and frustrating. First and foremost of these is the “sneaking” skill. In normal play, this skill is useless. A basic stick-and-move pattern is enough to overcome any monster in the game if you need to clear some space to do the work you came for, while all other monsters can be trivially bypassed simply by running past them if you’re not in the mood to fight.

In a nonviolent game, however, sneaking is invaluable given how much time you’ll be spending at gathering points uncomfortably close to roaming monsters. Moving about normally draws the monsters’ attention at a distance of about a quarter of the screen, and once they notice your presence, you won’t be mining or fishing or whatever it is you came to do. Sneaking, on the other hand, allows you to get much closer to your target without alerting them, making it possible to sidle up to a chunk of ore or a beachside tree and harvest it as the enemies wander nearby, completely unaware.

(Once engaged with a resource, the game treats you as if you were still in sneaking mode for purposes of enemy awareness, which is amusing when you’re playing a miner clanging away at mineral veins. It’s also funny when you finish your work and forget to resume sneaking afterward, forcing you to skedaddle away with your hard-earned resources. Suffice to say, this bit of comedy never happened during my normal playthrough, and made me laugh constantly as a pacifist.)

Certain areas that were nothing special on a regular playthrough are revealed as devious pieces of design to a pacifist. The Waterfall Cave has one short side passage consisting of three worms patrolling a narrow corridor that usually culminates in a round room with some Superior Marine Ore. In order to collect that ore during my Life as a miner, I had to play a tense game of stealth dodging on par with anything in Metal Gear Solid–one slip-up with any of the three worms, and they’d chase me back out of the corridor to start all over again as they returned to their positions. Or the beach in the Tortuga Archipelago, seemingly too thick with deadly crocodiles to fish–but at night, they fall asleep, letting you tiptoe your way through them and cast your line in peace.

Certain areas that were nothing special on a regular playthrough are revealed as devious pieces of design to a pacifist. The Waterfall Cave has one short side passage consisting of three worms patrolling a narrow corridor that usually culminates in a round room with some Superior Marine Ore. In order to collect that ore during my Life as a miner, I had to play a tense game of stealth dodging on par with anything in Metal Gear Solid–one slip-up with any of the three worms, and they’d chase me back out of the corridor to start all over again as they returned to their positions. Or the beach in the Tortuga Archipelago, seemingly too thick with deadly crocodiles to fish–but at night, they fall asleep, letting you tiptoe your way through them and cast your line in peace.

Not all of the game’s design rewards nonviolent play, alas. If I had to single out one aspect for criticism, it would be the artificial barriers within most of the game’s dungeons that poof out of existence once you’ve killed the nearby enemies. I already didn’t think much of these during my normal run, since there seems to be little point to forcing the player into combat when there are already several clear benefits (experience, item drops, space to work) to killing enemies as it stands.

During the nonviolence run, though, they were found so often in dungeons as to be downright teeth-grinding. The first time I went into the Subterranean Lake as a Woodcutter, I thought the challenges there would be impossible, until I reset the dungeon’s spawns a few times and found that there was a single, solitary tree that sometimes spawned before the kill gate. I fared even worse in the Lava Cave as an Angler; none of the Life’s challenges there can be completed at all without resorting to violence.

Yet in a perverse way, this too was rewarding. One thing I think games often get wrong when they try to implement moral choice is studiously preserve mechanical equivalence between the choices. In BioShock, for example, you’re not really sacrificing any power when you choose to save the Little Sisters rather than harvest them–you’re only trading short-term gains for long-term benefit. In real life, the virtuous path often has no reward, or is actively harmful, and so too is it with Fantasy Life. I came to appreciate the way that my pacifist Angler, prevented by principle from ever fishing the magma flows of the Lava Cave or the ice holes of Mt. Snowpeak, was forced to look past the prescribed challenges deemed appropriate to his rank and set out to find new challenges in places he had not been told to go. By the time my Angler was finally awarded the title of Master, he had already been fishing in places worthy of a Hero.

Yet in a perverse way, this too was rewarding. One thing I think games often get wrong when they try to implement moral choice is studiously preserve mechanical equivalence between the choices. In BioShock, for example, you’re not really sacrificing any power when you choose to save the Little Sisters rather than harvest them–you’re only trading short-term gains for long-term benefit. In real life, the virtuous path often has no reward, or is actively harmful, and so too is it with Fantasy Life. I came to appreciate the way that my pacifist Angler, prevented by principle from ever fishing the magma flows of the Lava Cave or the ice holes of Mt. Snowpeak, was forced to look past the prescribed challenges deemed appropriate to his rank and set out to find new challenges in places he had not been told to go. By the time my Angler was finally awarded the title of Master, he had already been fishing in places worthy of a Hero.

NONVIOLENCE IN THE ECONOMY

All gathering and crafting Lives inject value into the world; all labor is considered valuable. Materials that cost nothing to harvest gain value through the act of collecting them and can be sold at market. Materials that cost Dosh (the game’s currency) at market gain value through the act of crafting; a crafted item is always worth more at market than the sum of its materials. This virtuous economic cycle, unusual for an RPG, is what makes nonviolent play possible for a crafter; if they weren’t able to profit from their creations, they would be forced to sell flowers and seashells at a pittance to make ends meet. (In fact, this is essentially the “trade” practiced by the aforementioned callow youth; he collects forest mushrooms in lieu of taking up a Life.)

The combat Lives are an exception. Their labor is not valuable, at least not in the way of other Lives’ labor. A Woodcutter depends on the Blacksmith for his tools, and the Blacksmith relies on the Miner for her ore; both Lives purchase the fruits of other Lives and sell the fruits of their own. For players, though, violence can be sold–some NPCs offer rewards for killing a certain number of animals, and players can sell the items dropped by monsters–but, curiously, not purchased.

Though I mentioned in the rules of play that NPC allies can be recruited, this is never a monetary transaction. If an Angler could hire a Hunter or Paladin to look after him while he did his fishing, then the combat classes would have a clearly defined place in Reveria’s economy. But every last one of the recruitable NPCs volunteers their services freely, ready to join your party whenever you ask without compensation. This has the curious effect of devaluing violence in the world, an effect reinforced by its absence of a role in problem-solving during the game’s storyline.

Though I mentioned in the rules of play that NPC allies can be recruited, this is never a monetary transaction. If an Angler could hire a Hunter or Paladin to look after him while he did his fishing, then the combat classes would have a clearly defined place in Reveria’s economy. But every last one of the recruitable NPCs volunteers their services freely, ready to join your party whenever you ask without compensation. This has the curious effect of devaluing violence in the world, an effect reinforced by its absence of a role in problem-solving during the game’s storyline.

Even in my normal game, the combat Lives were always kept to their own enclaves, with little noticeable effect on the rest of the world. I went to market every day to buy sundries and materials; I’d sell the ore I’d collected or the equipment I’d crafted, then go either out into the field again, on the hunt for more minerals, or return to my fellow craftsmen to get back to the forge. My day-to-day business never took me anywhere near the Hunters’ camp or Paladins’ barracks. As a Miner, I would be nowhere without the Woodcutter to provide my pick’s haft and a Blacksmith to pound out a spike. But I had a dagger and was good enough with it to do my own killing; what value did a Mercenary provide?

One could theorize that it’s the Hunters and the Magicians of Reveria who keep the shops stocked with Hard Claws and Little Tails, but I sold my share of these at market in my normal game without ever dabbling in a dedicated combat class. There’s nothing stopping a “pure” Cook from taking her dagger and going out into the Grassy Plains to get her meat the hard way, but a “pure” Paladin doesn’t have the necessary skills or training to apply saw to tree. The economy of the world of Reveria simply doesn’t offer a niche to those whose sole talent is violence.

NONVIOLENCE BY DESIGN

After I made the choice to eschew violence in my second playthrough, I found the hand of the developers allowing (if not encouraging) it everywhere I looked. There are so many instances and moments throughout Fantasy Life where a decision the other way would have made a pacifist play style impossible. If gathering Lives weren’t permitted to gain advancement points for challenges they hadn’t yet unlocked, I would never have mastered Angler or Miner. If crafting Lives couldn’t draw on a wider variety of market selections through the Shopping+ unlockables, I’d never have mastered any of them, let alone all of them. And if the story didn’t provide peaceful resolutions for every mandatory “combat” scene, I’d never have finished the game at all.

After I made the choice to eschew violence in my second playthrough, I found the hand of the developers allowing (if not encouraging) it everywhere I looked. There are so many instances and moments throughout Fantasy Life where a decision the other way would have made a pacifist play style impossible. If gathering Lives weren’t permitted to gain advancement points for challenges they hadn’t yet unlocked, I would never have mastered Angler or Miner. If crafting Lives couldn’t draw on a wider variety of market selections through the Shopping+ unlockables, I’d never have mastered any of them, let alone all of them. And if the story didn’t provide peaceful resolutions for every mandatory “combat” scene, I’d never have finished the game at all.

These things don’t happen by accident. It took conscious choice and careful effort on Level 5’s part to ensure nonviolence had a place in their world. I guarantee you that at some point, somebody slipped up and made a snap decision that would have inadvertently prevented this style of play from working, and it took dedication for the designers not to shrug and say, “Oh well, it’s too late now.” The designers and the planners and the QA testers all believed in a nonviolent alternative, one that the game never even explicitly invites you to consider, and they all went the extra mile to make sure it was possible.

This choice goes beyond what kind of a game director Atsushi Kanno and his team wanted to make, and speaks to what kind of world they wanted to let the player to inhabit. It’s a common criticism of open-world games like Fantasy Life that the only interaction possible with the worlds’ inhabitants is violence. The usual rebuttal is to cite how complex and out-of-scope a truly living, breathing simulation of a world would be and that those developers are doing the best they can. But Fantasy Life shows this isn’t necessarily the only way. It proves by example that simply allowing a thing to exist, to let it go about its monstrous business unmolested, to both live and let live, is a powerful statement.