The Novelist: How Narrow The Gate

At 5 PM, Andrew got in touch and asked if my writeup of The Novelist was ready to review yet. It wasn’t; all I had was a document (novelist-notes.txt) where I’d jotted down some loose ideas. I told him I could have something ready by evening, but he said he’d need it by 8 or 9 if I wanted him to proofread it. Otherwise, his travel constraints meant he wouldn’t be able to review it until after the embargo lifted at 10 AM the next morning. Neither of us wanted to publish late, since creator Kent Hudson had been kind enough to provide us with early review code. But if I didn’t finish the review by 9 PM, our text would be unpolished, late, or both.

If I left work a bit early, I might be able to get a draft together in time, though I’d have to write fast and make up the work hours some other day. If I left at the normal time, I could write a draft and have somebody else review it, though that would mean publishing without Andrew seeing the text. Or I could decide that quality was more important than timeliness, write the draft on my own time, and wait until Andrew was in a better position to review it, which would have the unfortunate effect of possibly letting Kent down on his launch day. There was no solution that could satisfy all three of us.

This is the structure of every choice you make in The Novelist. Kent Hudson has sidestepped the trap of most binary choices in video games, which boil down to whether you want to be a saint or a villain, by turning them into ternary choices instead. Each option in the game is equally valid, but will only fully satisfy one of the three major characters; you might be able to compromise toward a second choice as well, but there’s no way to please everybody all of the time.

This is the structure of every choice you make in The Novelist. Kent Hudson has sidestepped the trap of most binary choices in video games, which boil down to whether you want to be a saint or a villain, by turning them into ternary choices instead. Each option in the game is equally valid, but will only fully satisfy one of the three major characters; you might be able to compromise toward a second choice as well, but there’s no way to please everybody all of the time.

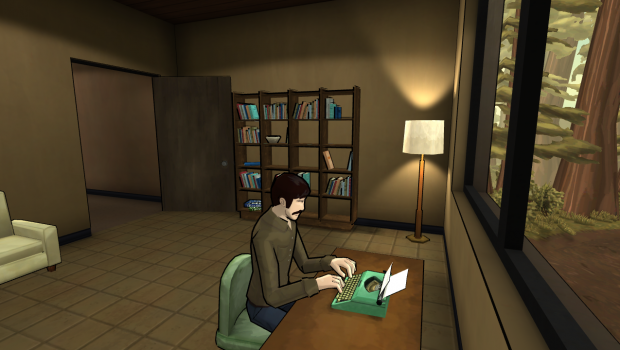

Those characters are Dan Kaplan, the titular novelist; his wife Linda; and their son Tommy. You play as a ghostly figure who follows them around the summer home where Dan has chosen to isolate himself while he writes his second novel. Every month of the summer vacation is divided into three scenarios, which require you to guide Dan through a series of decisions on how to spend his time and (sometimes) money.

At first, it seemed strange that the game consistently encourages the player to see things from Dan’s perspective, when he’s not a particularly better developed or more relatable character than his wife or son. The title of the game is a hint—it’s not called “Summer Home,” after all—and there’s also the way you, as a ghost, influence things only by whispering advice to Dan as he sleeps. The player is making the decisions, but it’s Dan who has all the agency.

That’s because ultimately, The Novelist is a game about work-life balance, an issue that’s lately loomed as large for game developers as injuries have for athletes or alcoholism has for writers. (Naturally, Dan has his own struggle with the bottle in one of the game’s mini-arcs.) Among the three major characters, the problem of work-life balance is uniquely his.

That’s because ultimately, The Novelist is a game about work-life balance, an issue that’s lately loomed as large for game developers as injuries have for athletes or alcoholism has for writers. (Naturally, Dan has his own struggle with the bottle in one of the game’s mini-arcs.) Among the three major characters, the problem of work-life balance is uniquely his.

It’s a common problem in creative fields. Unlike a steady office or retail job, where you do your work and then go home, a job in a creative field means you could always be doing more work. Work is fun, more often than not; something you started out as a hobby but ended up as a vocation. Making it your career just means you get to make money from the thing you love. When you’re not in the studio, it’s easy to let your passion take over your thoughts, because when you go back to work you only have what you bring with you.

I can attest that I’ve been so excited to receive a new project’s files that I drove to the office, at midnight, just to download, unzip, and catalogue them. I was ecstatic. I’ve done this more than once. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that some people are only too willing to pour literally all they have into their work, voluntarily turning their Pie Chart of Life into a solid circle. If you could spend all your time doing something you loved, why wouldn’t you?

Because there is more to life than work. And when that “more” comes in the form of living, breathing people, as it does for Dan, it’s irresponsible to neglect them. Yes, Dan is the breadwinner of the Kaplan family, and yes, their well-being is riding on his success, but their mental and spiritual health depends on his making time for them. Not all of us have our own spouses and children, but we all have family and friends. One of the most affecting mini-arcs has to do with who the Kaplans choose to let stay at their house one weekend, reminding the player that Dan’s decisions can affect more people than just the small circle we spend the whole game with. In the decade since I moved to California, I’ve only stayed over Christmas due to project deadlines once. The experience was painful enough that I’m determined never to repeat it.

Because there is more to life than work. And when that “more” comes in the form of living, breathing people, as it does for Dan, it’s irresponsible to neglect them. Yes, Dan is the breadwinner of the Kaplan family, and yes, their well-being is riding on his success, but their mental and spiritual health depends on his making time for them. Not all of us have our own spouses and children, but we all have family and friends. One of the most affecting mini-arcs has to do with who the Kaplans choose to let stay at their house one weekend, reminding the player that Dan’s decisions can affect more people than just the small circle we spend the whole game with. In the decade since I moved to California, I’ve only stayed over Christmas due to project deadlines once. The experience was painful enough that I’m determined never to repeat it.

“There are no statements here, only questions,” says Hudson of his game, and the Novelist is laudable for sticking to that principle. Truth be told, the somewhat tedious stealth mechanics add little to the experience, and the game is most affecting on “Story” difficulty—focusing on the Kaplans’ situation du jour instead of your own ghostly nature helps to bring the story’s dilemmas to the forefront. When all is said and done, after the ending you’ve chosen, the last unspoken question is the most important one of all: are you okay with how Dan ended up? If not, what needs to change for him?

For you?