Antichamber: An Antireview

This is not a review of Alexander Bruce’s Antichamber. Certainly, you could deconstruct the game and assign it point scores for things like sound and presentation. You could do the same for the Mona Lisa or Moonlight Sonata, too. Point scores are basically useful for distinguishing between grades of extruded industrial “product” and Antichamber is defiantly not “product.”

Released on PC, where weird indie games now sprout like mold, Antichamber takes exactly the opposite tack from your average AAA console game. There is no marketing-driven genre label like ACTION or FIRST-PERSON SHOOTER on the back of the box; there is no box. There is an icon in your Steam library with an intriguing little Escher loop built into the logo.

Boot it up, and you are thrown into a 3D box with wireframe walls. One side says “All You Need to Know,” and has a list of controls, options-and a timer, which has already started ticking. You look at the other walls, and see a sign titled “Exit.” You run towards it, and bash into an almost-invisible glass wall. Ha, you think. Cheeky bugger. And we’re off to the races.

Already, we have subverted or simply side-stepped much of what is repulsive and tedious about contemporary video gaming. Where is the 2-hour long hand-holding tutorial that explains the mechanics you already know ? When do we see the unskippable cutscenes filled with Hollywood explode-y stuff? What is the motivation for your plucky hero to proceed along their heavily-scripted path? And why is the EXIT right there? (And why did I pay money for this again?)

Well, here’s the thing about Antichamber: the game is the tutorial is the game is the tutorial. It is pure, abstract learning. You begin in the barest possible environment, to encourage an open mind and an abandonment of preconceptions. And from that point on, each new environment you encounter has the singular goal of teaching you something about how to negotiate it. You learn by playing and you play by learning. There is literally almost nothing else to it.

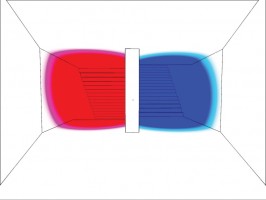

The first section brilliantly disposes of the standard first-person “corridor” mechanic (where players thrust ever forward to get to the next cutscene). The geometry of the environment is the crudest wireframe 3D, the sort you might remember from the old arcade game Battlezone, only updated in neon flat colors and disco lighting effects like neo-classic REZ. You run around a corner or two, and find a room which is split vertically into red and blue corridors. A sign on the wall says “A choice may be as simple as going left or right.” You keep running, and find yourself facing a room split vertically into red and blue corridors. Hang on…what? You go down the blue corridor and find yourself facing a room split vertically into red and blue corridors. Uh. If you are under-caffeinated, you might run the cycle a dozen more times, waiting for something to happen to you, for something to break into your experience, tell you what is going on, tell you what the objective is, COMFORT YOU, basically. But you don’t get jack shit. All you get is back to a room split vertically into red and blue corridors.

Eventually you give up and backtrack…whereupon you find yourself in an entirely different corridor from the one you entered. A sign on the wall says “When you return to where you have been, things aren’t always as you remembered.” The lesson? Non-linearity and expectation-confounding are the order of the day. Start dealing with it.

Fortune cookie wisdom to be sure, but thanks to ingenious warpings of geometry and logic, the player is forced to actualize the statement, internalize it, and above all, learn from it. The player will need this knowledge again, and much more besides. By forcing the player to discard everything they thought they knew, they force them to realize ‘”What I do know to be true is: Just this.” Again and again, until they have built a body of knowledge and experience and mind-bending geometrical trickery that enables them to find out what lies beyond that door named “Exit.” Certainly not “The End” of the game-you’ve already seen that door elsewhere. Oh yes, but the game enjoys jerking you about.

So it’s a puzzle game, then. But what puzzles! The sort that I cannot possibly spoil for you. The sort that make you scream “NOOOOOO!” when you realize the crushing horror of your predicament, the sheer absurdity of expecting you to do THAT when obviously you can only do THIS. The sort that make you try stupid shit that will never ever ever work but you can’t think of anything else right now so you do it anyway and then your synapses begin to fire a bit and wait a minute this isn’t quite so crazy after all and holy crap you did it worked exactly 100% according to plan, surely that’s the Nobel Prize committee on the line right now…

I tried so hard to break this game, to find ways to cheat and abuse my abilities to get around those obstacles in a way that the designer hadn’t anticipated. My tiny fists beat against the adamantium surfaces of creator Alexander Bruce’s giant glowing brain to no effect other than me doing exactly what he wanted me to do all along. This sentiment was usually reinforced by the pithy signs viewable after making progress to a new area. You know those brilliant bits at the end of Portal 1 and 2? That’s how I felt throughout most of Antichamber. Like someone was literally reading me like a book and then manipulating me like a marionette. It’s rare and eerie to share that kind of intimate connection with a game and its creator.

As much as it obsessed and enthralled me, there were a few shaky spots where I got badly stuck, or knew what to do but struggled to execute it. But less often than I expected, and far less than in most megabudget AAA titles. And after finishing the game and watching videos of others playing, I realized that the worst parts of my playthrough were because I picked the single daftest way of accomplishing a task that others breezed through in style. Turns out, not every learning experience the game has to offer is a brain-fizzing pleasure. Just most of them.

Could more be done with these concepts with a bigger team and budget? Yes and no. Valve in particular excels at taking raw gameplay mechanics and turning them into full-blown entertainment, usually by adding comic relief robot sidekicks, or hats. I am unconvinced that would make Antichamber any better. Perhaps a reactive electronic soundtrack, an ecstatic Daft Punk anthem? A pleasant enough dream, but difficult given the game’s fractured pacing. In any case, it is precisely because the learning environment is so reductivist and abstract that the player learns to focus on the game’s peculiar logic.

Antichamber is a tool designed for a very specific purpose: teaching you to play Antichamber. Adding anything to it would ultimately be subtractive. The only thing it needs is someone to play it-and that’s where you come in.